TRIPOLI, LIBYA – Right now, every corner of the globe is battling the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic. Hospitals in Europe and the United States are bursting at the seams, while African countries are beginning to see a sharp rise in the numbers of recorded cases. These countries are poised to form the next wave of this global crisis, and with far fewer resources than the West.

In Libya, the impending wave of COVID-19 cases is just one of a myriad of daily challenges to refugees and asylum seekers’ survival. This past Saturday, April 4, marked exactly one year since General Khalifa Haftar began his advance on the Libyan capital, and since then the country has been engulfed in civil war. The economy is crippled, the displaced live in decrepit apartments and abandoned construction sites, packing dozens of people into concrete boxes with dirt floors and no doors. Militias patrol the streets, and gangs rob and kill civilians. There are regular cuts in running water and electricity in dense urban areas. In “official” detention centers, asylum seekers find themselves packed in the hundreds into open “hangars” where past outbreaks of respiratory illnesses like TB have already taken dozens of lives. And in “unofficial” detention centers, human traffickers hold refugees hostage, torturing them for ransom money from their loved ones abroad. These conditions are so dire that Human Rights Watch released a report warning that if COVID-19 reaches these centers, it will result in mass casualties of asylum seekers from Eritrea, Sudan, Somalia, Ethiopia, and across the continent. At this time, Libya has confirmed 19 cases of COVID-19. However, despite the pandemic, the conflict has only intensified. On April 6, heavy shelling hit Tripoli’s Al Khadra General Hospital, injuring at least one health worker. According to a statement by OCHA, as of March 2020, 27 health facilities have been damaged in the conflict, 14 facilities have closed, and another 23 health facilities are at risk of closing as the front lines continue to shift.

A month before General Haftar and the Libyan National Army (LNA) launched an assault on Tripoli and its UN-backed Government National Accord (GNA) last year, I received my first message from an asylum seeker in a Libyan prison. He was in the Qaser Bin Ghashir detention center. Though I did not know it at the time, it was only weeks away from militia fighters storming the facility and shooting indiscriminately into the crowd. The Eritrean detainees in the facility had refused to cease their Easter prayers, angering the soldiers. This was to be my first painful glimpse into the tragedy of refugees in Libya.

Asylum seekers left homeless after the bombing of the Tajoura detention center sleep outside the rubble of the prison for a week without aid

UNHCR’s urban assistance package consists of a one-time cash payment of 450 Libyan Dinar (about $300) and an assortment of in-kind goods. Landlords in the neighborhoods with a heavy asylum seeker presence know these people lack recourse and take advantage of their situation, charging between 300-400 Dinar for a concrete room with no doors, no bathroom, and a dirt floor. Urban asylum seekers without protection fall victim to robberies and kidnappings. In January,two Eritrean asylum seekers Kiflay Fishatsion and Freselam Mengesha were found killed in their Tripoli apartment, just ten days after they left the GDF and joined the urban program.

Asylum Seekers tend to the wounded following an attack on the Qaser Bin Ghashir detention center, April 23 2019

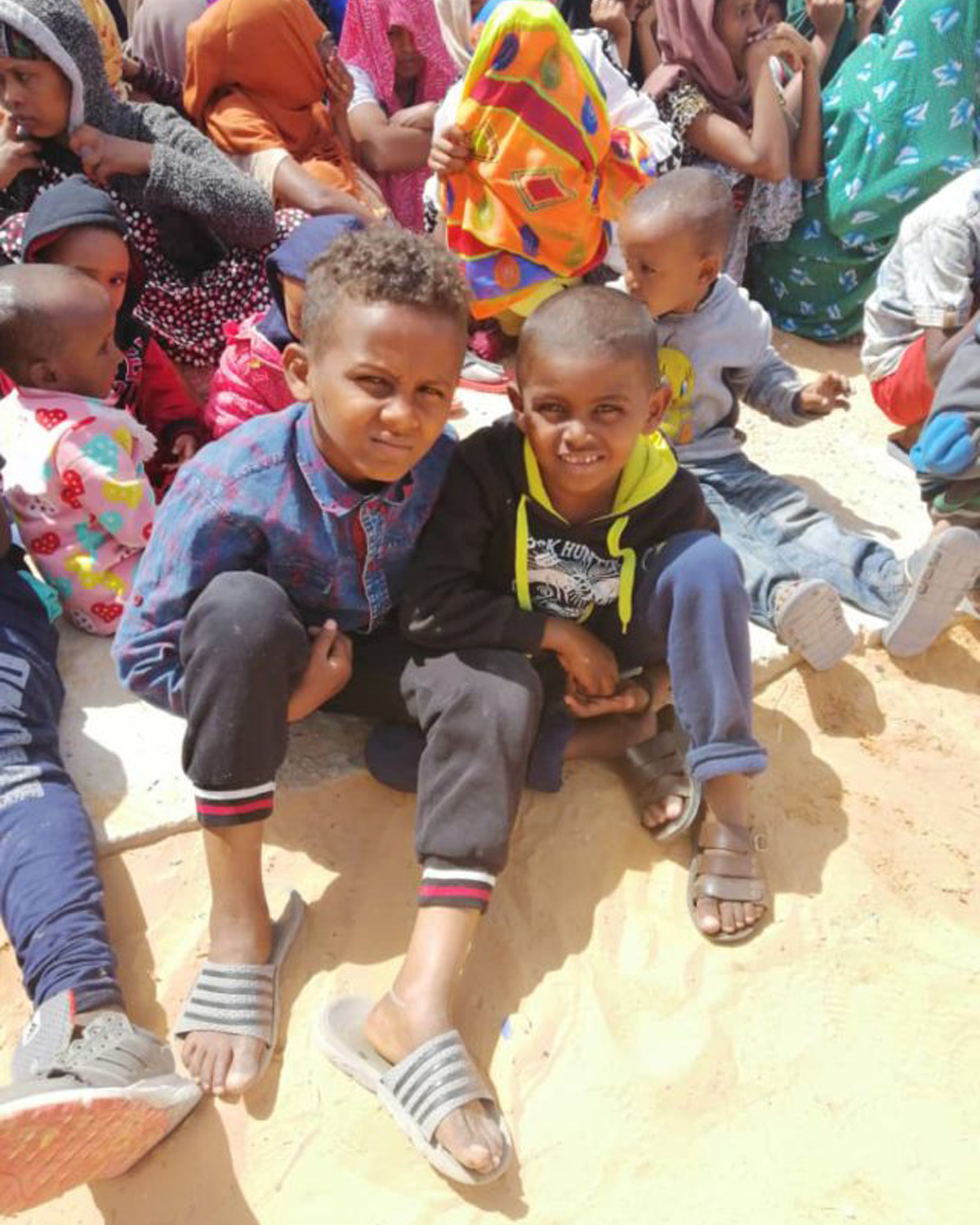

This is just the most recent of a string of civil wars, since Moammar Ghaddafi was ousted in 2011, but it is one of the most severe. In the past year alone, more than 355,000 Libyans have been internally displaced by the conflict. These Libyan civilians have had their lives torn apart, they have been separated from loved ones, and many have lost everything. But for the people whose lives I’ve been documenting, conditions are even more dire. Asylum seekers from across Sub-Saharan Africa have, for more than a decade, travelled to Libya and into the belly of a warzone, escaping the persecution, violence and torture they experienced back home. Once inside the conflict, they lack the resources, family support network, and freedom of movement necessary to escape.

This is the struggle of an estimated 600,000 asylum seekers and migrants currently residing in the country. Of this total, 47,600 have registered with the authorities as asylum seekers, and about 3,000 live in captivity in immigration detention centers. These individuals hail mainly from Eritrea, Sudan, Ethiopia and Somalia, together with smaller numbers from across West Africa and the Sahel. Many would be classified as refugees under international law and qualify for protection if this was something Libyan laws recognized. However, according to Libya’s Department for Combating Illegal Migration (DCIM) any individual who has crossed an international border without a visa is guilty of an immigration violation regardless of their reasons, and can be punished with indefinite incarceration.

Many of the asylum seekers incarcerated in Libya today were intercepted at sea by the Libyan Coast Guard, thanks to an agreement signed with Italy in 2017 – backed by the EU – to train and fund the operation. This deal aimed to stem migration immediately off of Libyan shores before asylum seekers could reach international waters, where rescue boats run by aid organizations can save people in distress and disembark at European shores. And while arrivals in Europe have decreased drastically since then, the number of Libyan Coast Guard interceptions has skyrocketed. In the first two weeks of January alone, almost 1,000 asylum seekers were captured at sea and returned to Libyan shores. Many of these people are now under indefinite imprisonment in official detention centers, unreachable in the Sharah Zawiya processing center (where refugees report being detained for months before collecting ransom payments). According to the IOM, authorities are still unable to account for 600 of these individuals intercepted at sea.

Most of the 11 “official” detention centers in Libya operate under the jurisdiction of the GNA’s Department for Combating Illegal Migration (DCIM), mainly around the capital city of Tripoli. Others lie in LNA territory, while another estimated 800 asylum seekers are currently held in “unofficial” detention centers run by traffickers and militias who do not allow UNHCR or other partners on the ground any access whatsoever. Conditions in official detention centers are negligent at best and abusive at worst, as asylum seekers sleep on mats on the concrete floor, their bedding infested with insects. Hundreds are under treatment for TB, and in the Zintan detention center alone, there were at least 22 deaths last year from the disease. An Eritrean detainee in the Zintan facility explained to me that “Living in Zintan is like living in a grave. It is a hell which I cannot explain. We have lost 22 people here within 7 months to disease, and we have more than 100 TB patients in need of medical help.”

Refugees in the Zintan detention center, where the healthy are forced to share overcrowded accommodations with those under treatment for TB

In these centers, food is scarce, and saline tap water often replaces clean water when filters break down, resulting in ongoing kidney problems for detainees. A Sudanese detainee from the Darfur region explained that, “The problem of drinking water reached the extent of our diseases, the pain in the abdomen, especially in the kidneys, urinary tract infections and burning of the urine, so that I can no longer urinate. Now for months I drink the salt water of the Mediterranean, I feel like we are going to perish, many refugees are bedridden with deteriorating health, malnutrition. I suffer from acute kidney failure, I can no longer sleep at night from the intensity of pain.” Women frequently face sexual abuse, and those who become pregnant from their captors must give birth in their concrete cell without proper medical attention. Some reported miscarrying due to the harsh conditions.

A female detainee in Qaser Bin Ghashir detention center comforts her infant child, detained in the facility with her, days before the prison was attacked by militia fighters.

For asylum seekers in unofficial detention centers, the situation deteriorates further. The tactics in these facilities often mirror those used in the Sinai. Detainees have a bounty placed on their heads of $10,000 or more, and they are tortured until their friends and family abroad pay for their release or until they are sold to other traffickers for a profit. One Somali man whose brother fell victim to these centers relayed that, “From December 2017 until January 2018 I lived in Khoms detention center, in that place I lost my brother. The police sold 12 Eritreans and 7 Somalis, one of them included my brother. He was taken to Bani Walid…there were 97 Somali people kidnapped by Libyans in Bani Walid, they asked for more than $20,000 ransom and 8 of them died from torture. My brother was one of them.”

With these nightmarish conditions in detention centers, it is tempting to consider the urban environment safer. However, asylum seekers in the detention center tell me they fear being sent out of the prisons into the unprotected urban setting, where they are at a heightened risk of extortion by gangs, militias and even Libyan officials, as well as kidnappings by human traffickers. Exemplifying this fact is the case of the Gathering and Departure Facility (GDF), which, until recently, was managed by UNHCR in Tripoli. The facility was designed to be a short-term transit center for the processing of individuals with an evacuation process pending. However, in July 2019, a detention center in the Tajoura suburb outside Tripoli was hit by airstrikes, leaving at least 53 Eritrean and Sudanese asylum seekers dead. The 400 survivors walked on foot to the GDF and admitted themselves into the facility, asking UNHCR for protection. In October 2019, another group, this time from the Abu Selim detention center, escaped their imprisonment and followed suit, sleeping in the street in front of the GDF for three days before being allowed entry. The number of individuals in the GDF swelled to 1,200 despite having a 700-person capacity, and conditions deteriorated until the security threats caused UNHCR to abandon the facility in January. They offered an urban assistance package to anyone who agreed to leave the facility and now only about 150 refugees remain there – mostly Tajoura survivors.

The aftermath after LNA airstrikes targeting a nearby GNA base struck the Tajoura detention center, killing at least 53 asylum seekers.

Asylum seekers left homeless after the bombing of the Tajoura detention center sleep outside the rubble of the prison for a week without aid

UNHCR’s urban assistance package consists of a one-time cash payment of 450 Libyan Dinar (about $300) and an assortment of in-kind goods. Landlords in the neighborhoods with a heavy asylum seeker presence know these people lack recourse and take advantage of their situation, charging between 300-400 Dinar for a concrete room with no doors, no bathroom, and a dirt floor. Urban asylum seekers without protection fall victim to robberies and kidnappings. In January, two Eritrean asylum seekers Kiflay Fishatsion and Freselam Mengesha were found killed in their Tripoli apartment, just ten days after they left the GDF and joined the urban program.

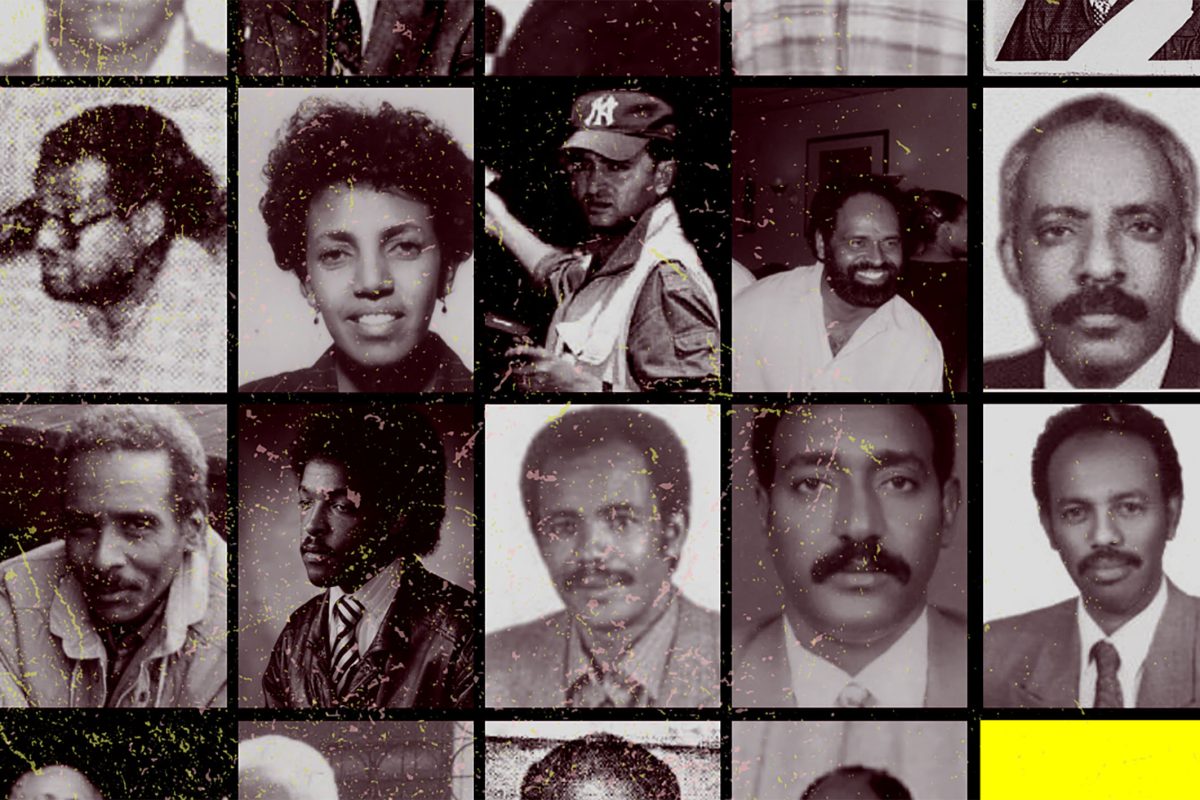

Kiflay Fishatsion

Freselam Mengesha

To this day, no alternative solutions have been offered to the nightmare of detention or to the dangerous and woefully insufficient urban program. Evacuations remain a far-reaching dream for most, as only 2,800 resettlement spaces have been pledged for Libyan evacuees over the entirety of 2020. Due to processing requirements, only 900 of these spaces are dedicated to direct evacuations from Libya; the remainder must be processed through the transit mechanisms in Niger and Rwanda where slow processing times and overcrowding have already led to unrest. And without improvements in asylum seekers? home countries, we will see more people continue to flee in search of protection.

Refugees in Libya hold a demonstration, asking for evacuations or for a safe shelter instead of being evicted to the urban program.

Because those refugees who have spent years in Libya waiting patiently to be evacuated are losing hope, we will undoubtedly see increased numbers of people willing to risk their lives on the Mediterranean Sea. In the words of one Eritrean asylum seeker who left the GDF three weeks ago and is planning to try his luck on the dangerous tides, “I have lived in Libya more than two years. Your chance is the sea – God willing.”

How can you help?

Those of us lucky enough to have a safe home in a Western country can sometimes feel helpless when we hear about the tragic events unfolding on the other side of the world. However, it is precisely because we live in a democracy, with elected officials who are accountable to us, that we are able to help through advocacy and community organizing.

Contact your Members of Congress. – If you live in the United States, you can use “this link” to find your representative and their contact details. Call them, email them, tweet them, even set up an in-district meeting with them in person (once it is safe to do so again). I used to believe that only lobbyists had access to these policymakers, but that is far from the truth. Members of Congress love to hear from their constituents about what matters most to them, and hearing from you about this critical issue makes all the difference. Ask them to support bills that can help asylum seekers in Libya, such as the Libya Stabilization Act, which includes specific text about humanitarian support for refugees and asylum seekers from Sub-Saharan Africa.

Write an op-ed and send it to your local newspaper. – Guides like “this one” advise on how to write these types of articles, how long they should be, what to focus on, and how to submit them for publication. By reaching a wider audience, you can help to spread vital awareness about the situation in Libya. Speaking to those who already agree with us is not enough; we must also reach out to those who disagree or have not heard about the issues at all, and explain to them why they should care.

Advocate for evacuations. – According to UNHCR’s latest “Global Trends” statistics, there are currently more than 70.8 million displaced people in the world today. Of that number, 26 million have been legally recognized as refugees, and another 3.5 million are currently seeking asylum (the rest are internally displaced inside their home country). Yet, in 2019, just over 63,000 refugees worldwide were resettled to a safe country. This is because places like the United States have been drastically reducing resettlement quotas each year. In President Obama’s last year in office, he set the 2017 “Presidential Determination”, or refugee resettlement ceiling, at 110,000 people. Today that number has been slashed to a mere 18,000. UNHCR cannot resettle refugees without countries first offering resettlement spaces. Therefore each one of us contact our Members of Congress and tell them to restore a robust refugee resettlement program.

Give Eritrean refugees a safe home to return to. – Every day thousands flee Eritrea in search of safety and security outside the country. Families are torn apart and scattered around the world, community ties are broken, and traffickers inflict deep trauma from which it will take generations to recover. By joining – Reclaim Eritrea, you can take action in your community and online to help restore justice and democracy for loved ones back home. If we can create a safe home for them once more, then refugees will no longer risk their lives to reach safer shores and can begin to rebuild their lives back home in Eritrea.

Refugees can only be freed from Libya if there are safe places for them to go, and right now, these spaces are severely lacking. But it is in our power to change this. If we organize together, with one united voice, there is nothing we cannot accomplish.